I think Anne Rice’s “Vampire Chronicles” series didn’t become really big until the publication of The Vampire Lestat in 1985, but look at the copyright date on this book, the first in the series: 1976! Remember the controversy over whether Tom Cruise was an appropriate choice to play Lestat in the 1994 film adaptation – in its pre-World Wide Web way as big a casting brouhaha as anything involving the Twilight cast today – and now realize that this book was published 18 years earlier. Today it seems like you can’t throw a rock without hitting a couple of writers getting rich off a series of vampire novels, but all of these modern vampires owe their popularity – and arguably their very existence – to Anne Rice and Interview With the Vampire This is where it began.

And it’s actually a pretty good book. I first read it around the time of the film (though I never saw the film), and found it engaging and compelling. Which is more than I can say for the sequel, as I thought The Vampire Lestat was borderline-unreadable (and way too long), so I stopped there. But Interview stands on its own just fine.

The vampire of the title is Louis, who is being interviewed by a young reporter in present-day San Francisco (using a tape recorder, since the “present day” is the 1970s here). Relating his life story, Louis was a plantation owner in Louisiana in the late 18th century, when he is attacked and turned into a vampire by Lestat, who desires to use Louis to live a comfortable life of leisure. Lestat is a mercurial personality, filled with anger and ego, who lets Louis know only a little about being a vampire in order to keep Louis tied to him. When Louis shows signs of wanting to leave, Lestat tricks him into helping him turn a 5-year-old girl, Claudia, into a vampire. This ultimately proves to be Lestat’s undoing, as Claudia – who never ages – chafes after several decades at Lestat’s dominance of their triad and eventually schemes to free herself and Louis from Lestat. The pair leave the United States in the late 19th century and head to Europe.

After a period in eastern Europe learning the sad fate that befalls some vampires, they end up in Paris, where they meet a coven of vampires who have set themselves up as a high-class theater. They are nominally led by Armand, who believes himself to be the oldest vampire on Earth, and who wishes to anchor himself to Louis so that he can avoid the disorientation of living through the changing centuries which causes most vampires to ultimately kill themselves. He and Louis plan to allow Claudia to live on her own, but other forces within the theater troupe engineer a series of events leading to tragedy for our heroes and everyone around them.

There’s a lot to like about Interview. For the science fiction fan, there’s the fact that Rice pared down the mythological trappings of the vampire, discarding many elements which felt superfluous (the vulnerability to crosses and garlic, for instance), turning them into predatory creatures of the night. She outlined the mechanism through which humans are turned into vampires, thus explaining why the world isn’t overrun by the creatures (vampires need to deliberately act to transform someone), and even explained why vampires eventually die off. While obviously not everything about a vampire can “make sense”, getting down to the essentials – the blood thirst, the vulnerability to the sun, the strength, speed and heightened senses, and the immortality – makes them terrifying creatures while also tragic ones.

Rice of course also brought the sense of gothic romance which pervades the genre today. While homoeroticism pervades the scenes between Louis and Lestat, and later Lestat and Armand, in a broader sense it’s raw passion and the denial of consummation of that passion which characterizes Rice’s vampires: They react viscerally to the deaths of their victims, moved as much by the shared experience (or what they imagine is the victim’s experience) as the need for their blood. And they cling to each other fervently because there are so few of their kind, and after just a few decades they can no longer relate to mere mortal humans. They are sexless, and the homoerotic overtones of their relationships are I think largely driven by their strong passions towards whomever they connect with than by any homosexual tendencies. But because their motivations are different from humans, their expressions of their desires are natural to them but seem strange to us, inasmuch as they are inhuman entities in human form.

Louis is an awkward protagonist, as he’s what an acquaintance of mine would term a “wussbag”: He’s not a very active character, has trouble making decisions for himself and is easily overwhelmed by stronger personalities, of which there are many around him. Subservient to Lestat, he is repulsed by what he has to do as a vampire to live, and even more repelled by Lestat’s cavalier attitude toward the same. Enthralled by Claudia, he does her bidding despite her being even more alien than Lestat, having never been grounded in human morality before being turned. Armand is less reprehensible but no less domineering, just a softer touch.

But the story is still wholly Louis’; fundamentally, it’s about his eventual fall, though it takes more than a century. He initially resists embracing his vampiric nature, preferring to survive by killing animals, but he eventually gives in. He doesn’t have the courage to kill himself, especially once he has the responsibility to care for Claudia. Having thought he’s finally found a place where he belongs, with the theater troupe, the climax of the story sees him lose everything he cares about, and drives him to finally take charge and retaliate against the parties responsible. He destroys the last bits of his soul in the process, and becomes numb, wandering the world with Armand but no longer seeing or feeling the things around him. His downfall becomes complete in the final chapters as he wraps up his interview in the present day.

It’s hard to say that Louis – or anyone in the book – is an admirable character. Reading about these characters is more like seeing a slow-motion train wreck, played out over decades. While I usually can’t relate to books whose characters I can’t relate to, Rice makes the characters human enough, and the exploration of their world and lives chewy enough on an intellectual and emotional level to keep you reading. Inasmuch as the book is narrated by a vampire, the characters come off a little more sympathetically than they would otherwise, but Rice remains detached from the question of whether vampires are morally reprehensible and whether they can be judged by the same standards as ordinary humans. Of course they can be, but making those judgments is up to the reader, which I think is one of the book’s strengths.

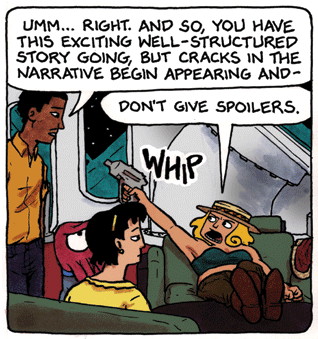

A friend of mine thinks this is a terrible book, poorly structured and featuring loathsome characters, only mildly redeemed through some well-written passages. I think it’s much better than that, if not quite the pop classic it’s become in the last generation, but well worth reading, especially to provide some historical context for today’s vampire mania. Indeed, for me this is all the vampire fiction I feel the need to read.